This is the first in a suite of five scenarios developed by Aleph Insights, designed with the following question in mind:

“What will the US government’s principal strategic priorities be between 2017 and 2020?”

More background on the scenario development process, including caveats about scenario interpretation, is here. This is the baseline scenario. The four alternative scenarios are Atlas Hugged, Fear and Loathing in Everywhere, We Need to Talk about Donald, and Catch SSBN-22.

Scenario Narrative

After one of the strangest elections in US history, President Trump arrived in office on 20 January 2017 on a mandate to ‘make America great again’, and a promise to be a ‘President for all Americans’, but with few in the way of concrete and credible policy promises. Trump’s first cabinet was a mix of loyal Republican operators, compensating somewhat for his own lack of political experience, and ‘Trump people’ - a cadre of business leaders and former associates whom he believed could help him get things done in the Washington jungle.

In terms of style, Trump has wavered between ‘Presidential’, ‘straight-talking’, and ‘gaffe-prone’. He and his family (to whom he has divested his business interests, albeit temporarily) have continued to be a ‘story’ since he took office. Various financial scandals and sexual harassment suits have emerged, but have bounced off him in a way which eluded previous Presidents affected by such things. Despite his age - the oldest President ever elected - Trump has remained healthy and energetic throughout his first term.

Economically, Trump has done his best to deliver for what he sees as his core supporters. A lowering of business rates, new investment subsidies and tax breaks for manufacturers, and a reining-in of environmental and commercial regulation, have boosted industrial output growth, although irreversible technological factors mean that employment in the sector has not kept pace. Trump has honoured his promise to increase military spending, and the defence budget has risen by $30bn a year, with missile defence being reinvigorated as a priority. Although looking financially competent is an important personal goal, balancing the books hasn’t been an overriding priority for Trump compared to boosting jobs, and government debt has increased year-on-year for the last four years.

Great Again

(photo: Gage Skidmore)

In social and domestic policy areas, Trump has also tried to deliver on his promises - kinda. The ‘wall’ has ended up for most of its length as a double fence, and Mexico hasn’t paid for it. The ‘repeal’ of Obamacare turned into an ‘amendment’ that removed mandatory insurance but kept most of the key provisions. Immigration controls have been tightened, particularly from unstable parts of the world - inevitably focusing on the Middle East - but the ‘complete shutdown on Muslims entering the US’ hasn’t been enacted due to recognition of its total unworkability. And Hillary Clinton remains at liberty.

On other sensitive domestic issues - abortion, gun control, rights for gay and transgender people, marijuana legalisation - the Trump administration has broadly avoided taking sides by advocating the rights of individual states to determine their own laws. Despite the fears of some of his liberal opponents, Trump has had no appetite to expend political capital either on introducing or repealing any Federal legislation covering these tricky issues.

President Trump has enjoyed the limelight of the international stage. His diplomatic style is based on personal relationships rather than alignment of national interests, and his focus has been on ‘getting a good deal’ for the US. Trump has picked his fights carefully, tempering populism with pragmatism, and has avoided endangering access to global markets to any countries or in any sectors that really matter to the US economy. In 2017, the US, Canada and Mexico formally began renegotiating NAFTA, widely blamed by many Trump supporters for US job losses. But besides a few high-profile protectionist measures for specific industries (including tariffs on non-US-produced cars and hydrocarbons, and tax breaks for US companies operating at home) none of the three countries have any real appetite to reduce free trade across the board, and as of 2020 the new deal is still officially being worked out.

Regarding international relations, a key early priority for Trump - on the strong advice of his military chiefs - was to affirm the US’s support to NATO, albeit with some lecturing about other nations paying their fair share. To an extent, however, tensions with Russia have eased because of the personal rapport between Trump and Putin, and the two countries have co-operated somewhat in the Middle East and in the sharing of counterterrorism intelligence. Overall, Trump’s administration has been less interventionist, and has made little fuss over human rights abuses or environmental degradation in other countries. Relations with the EU have been publicly frosty, not helped by Trump’s reinvigoration of the ‘special relationship’ with the UK in the run-up to its exit from the EU in 2019 which included some high-profile (though limited) trade pledges. Trump has used publicly competitive language regarding China, although relations are smooth behind the scenes.

In Washington DC, there was something of a party atmosphere in 2017. The Republicans went into the new administration riding high, with control of the White House and the Capitol, and a soon-to-be-balanced Supreme Court. It is true that for a vocal few in the GOP - its traditionalist, intellectual establishment - Trump is seen as a disaster: an embodied legitimisation of electoral nastiness, steered from below by a hard-to-control mob; a populist with no long-term strategy who will destroy the party when he fails to deliver on his unfulfillable promises. But for most Republicans, any concerns about Trump’s temperament were quickly swept under the carpet in the aftermath of the election, and GOP representatives were queuing up to be seen shaking hands with the new POTUS.

For the Democrats, however, the 2016 election ushered in a period of soul-searching about the loss of the traditional support base, and the party has moved somewhat to the left, talking more about workers rights, abuses by big business, and social cohesion. The Democrats remain committed to progressive values and are searching - so far in vain - for the next JFK. The 2018 mid-term election handed the House back to the Democrats with a small (224 to 211) majority, representing disillusionment with and apathy towards Trump from some of the 2016 voters.

Away from the Hill, the country is more divided than ever by 2020. An anti-Trump ‘movement’ of sorts has emerged from the loose coalescing of various liberal political and protest groups. But the Democratic party is not the primary focus or spearhead of this movement; instead its expression is mainly online and its figureheads include fringe politicians, Silicon Valley CEOs and YouTube gurus. ‘Resistance’ to the government in these forums takes various forms, including concerted assertions of digital and online rights including freedom of expression, evasion of US government intelligence collection efforts, cyberattacks and the co-ordination of assistance to illegal immigrants.

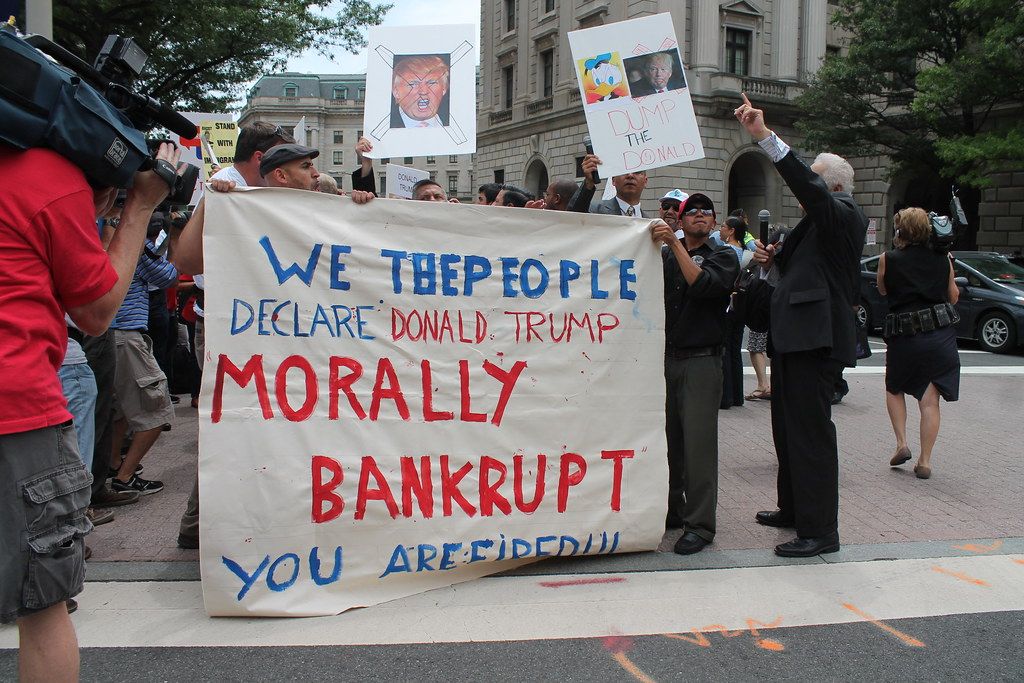

No Thanks

(photo: Elvert Barnes Protest Photography)

Real-world expressions of unrest remain sporadic. Black Lives Matter, and associated organisations including those representing Latinos, have become more vocal, and minorities express higher levels of fearfulness in Trump’s America. Riots in response to killings by police have become slightly more frequent, with a changed narrative that places institutional oppression at a national, rather than local, level. An incident in 2017 in which a Hispanic family was killed by a vigilante group for failing to stop at a ‘checkpoint’ has raised perceptions of a deepening and dangerous divide. President Trump has repeatedly condemned racial violence, but a small minority of his supporters nevertheless feel emboldened by the message that they have read into his 2016 electoral victory.

In contrast to the President’s pre-election fearmongering, Islamist terrorism has been largely a non-issue for the last four years. Two avowedly Islamist-inspired deadly attacks have occurred (a sniper attack on a shopping mall in 2017, and the bombing of an Army base in 2019) but most low-level political violence in the US continues to be associated with conservative and right-wing groups (including attacks on abortion centres and mosques). Statistically speaking, Trump’s presidency has had no significant impact on Islamist or any other form of terrorism in the US, despite popular narratives - on both sides - linking the two phenomena.

The 2020 elections are approaching. Despite the fears of his detractors, and the hopes of his more-fanatical supporters, Trump’s first term has been largely uneventful in terms of national policy initiatives or crises. The polls once again suggest a close race.

Policy Implications

Donald Trump’s main challenge has been to deliver on his promises to, and so retain the support of, the ‘middle Americans’ who deserted the Democrats in 2016. His focus has been on delivering economic growth, and particularly higher employment, with a mixture of tweaks to the tax and benefits system and a few high-profile initiatives. The US is neither significantly greater nor significantly less great than in 2016: it is not a new Jerusalem, but the world hasn’t ended either.

(Read the first alternative scenario: Atlas Hugged.)