The 'ignorance' theory of analytical confidence proposes that it is negatively related to the amount of information which you think exists, but which you haven't seen. The idea is that if you've assimilated a high proportion of the available information, you'll have more confidence in your probabilistic judgements than if you've only assimilated a small proportion of it. We've seen that this isn't a coherent idea, since measures of information (the converse of ignorance) are either encapsulated by probability (the information-theoretical definition) or are vulnerable to arbitrary manipulation using redundant material (as with the 'in-tray' model).

The 'expected value' theory that we looked at last time is an attempted refinement of the 'ignorance' theory that relates confidence not to how much information is as-yet untapped (this is implicitly captured by a statement's probability), but to how valuable that information is likely to be, which depends on current uncertainty and the benefits and risks associated with the decision that needs to be made.

The 'expected cost' theory, which is the last one we'll be looking at in this series, adds an extra dimension to this theory by incorporating the expected cost of information. The idea is that if new information is relatively costly, we will have more confidence than if new information is relatively cheap. This theory captures the same intuition driving the 'ignorance' theory - that confidence is about analytical 'due diligence' - but in a more-sophisticated way. How does it stand up to closer examination?

Is it coherent?

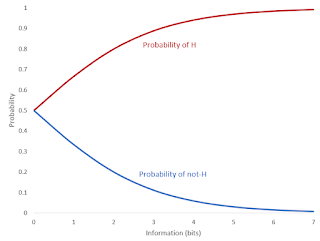

It is meaningful to talk about the expected cost of new information, provided we are precise enough in our definition of 'information'. The 'units' that information theory deals in are called 'bits' (a number of exotic-sounding alternatives have been put forward, including the Hartley, the crumb, and the doublet but they all do fundamentally the same thing). A bit of information is the amount that would, if received, effectively double (or halve) the odds ratio of a hypothesis. We can therefore talk about the 'expected cost per bit' of future information and mean something both real and distinct from probability.

Wikipedia: the low-hanging fruit of the information orchard

'Cost' does not always (or indeed usually) have to mean financial cost. Collecting information has an indirect time cost, and may have 'psychic' costs - the technical term for the unpleasant mental effort involved in consciously assimilating and processing information. The cost of information is not, in practice, usually constant: each unit is likely to cost more than its predecessor, assuming information is being collected in a roughly sensible way so that the low-hanging informational fruit (Wikipedia, the paper, what your colleague thinks) is picked before the harder-to-reach stuff (academic journals, paywalled data, secret intelligence).

Additional bits of information push the probability of a hypothesis

closer to 0 or 1, but at a diminishing rate. The two lines are

reflections of one another, because the probability of something

being true and the probability of it being false must add up to one. The rising marginal cost of information (per bit) is mirrored by the diminishing marginal value of information (per bit). As we saw when we looked at the 'expected value' theory, information exhibits diminishing returns in terms of the expected value of a decision. Adding additional bits of information changes the (decimal) probability of a hypothesis by ever-decreasing amounts as it approaches either 0 or 1. Since expected rewards (or costs) of a decision are (more or less) linearly-related to the decimal probability, each subsequent bit of information is worth less than the previous bit.

This means that if we bolt the 'expected value' and 'expected cost' theories together, we get a theory of confidence that turns it neatly into an optimal information-searching metric. Optimal information searching means continuing to collect information until the benefits of continuing to do so are outweighed by the cost; at that point, you should make a decision. If 'confidence' is higher when the expected value of new information is low, or its cost is high, we will tend to see confidence rising as new information comes in, because of diminishing returns and rising costs, until we are at a point where further investigation would be counter-productive.

The 'expected cost' theory also has an appealing link to a metaphysical distinction, often made by intelligence analysts, between 'secrets' and 'mysteries'. 'Secrets' are things that someone knows (but not you), while 'mysteries' are things that no-one knows, and in broad terms, intelligence analysts feel that their job is to unearth or make inferences about secrets, but not necessarily to worry about mysteries. This distinction, of course, has nothing other than a very superficial foundation: what makes information contained in a human brain any more special than that contained in any other system? But when situated in a more general theory about the cost of obtaining information, it begins to make some sense; assuming it's relatively-easy to get information out of a human (compared to, say, getting it out of seismic activity or the economy), the distinction between secrets and mysteries maps neatly onto the distinction between cheap information and expensive information.

Does it accord with usage?

In general, analysts seem not to think that their appraisal of confidence is connected to the expected cost of further information. One of the questions in our survey was designed to test the connection between consequence, cost and confidence; it concerned the possibility of a bridge failure in either an isolated or a busy location, and one of the variables was the cost of additional information (a quick site visit compared to an expensive structural survey). The consequences mattered: confidence was lower when the bridge was on a busy commuter route. But the cost made no difference to people's confidence assessments. Just as tellingly, no-one proposed a cost-driven measure of confidence when given the opportunity to define it in their own words.

Is it decision-relevant?

The expected cost of further information is decision-relevant. As laid out above, it is one half of the equation defining optimal information searching (the other being the expected value of that information).

Summary

The 'expected cost' theory of confidence is both decision-relevant and conceptually coherent. Its only drawback is that nobody believes that it's actually what they mean by 'confidence'.

In the next - and final - post in this series, we'll summarise the arguments and discuss what they mean for the prospects of a standard, cogent, workable metric that could be used by analysts to communicate confidence to customers alongside their probabilistic judgements.