In the last post, we examined the 'Information' and 'Ignorance' theories of analytical confidence. In this post, we'll look at the 'Quality' Theory of analytical confidence.

The 'Quality' theory says that 'confidence' represents some kind of metric capturing the overall soundness of the evidence-base and analytical process on which a judgement is founded. So a high-confidence judgement will be one that uses multiple sources, randomised trials, robust statistical methods, high-quality data and so on. A low-confidence judgement will be one that uses sparse or untested sources, bias-prone protocols, anecdotal evidence and patchy or dirty data.

"And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not,

shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand"

Photo: M Etherington As with all these theories, we'll put it to three tests: is it coherent, does it accord with analysts' usage, and is it decision-relevant? We'll tackle these in a different order than usual, because it's hard to assess the theory's coherence without understanding what it means when people refer to it.

Does it accord with analysts' usage?

A number of organisations provide interpretations of 'confidence' that embody the 'quality' theory. For example, the US Directorate of National Intelligence provides the following guidance:

"Confidence in Assessments. Our assessments and estimates are supported by information that varies in scope, quality and sourcing. Consequently, we ascribe high, moderate, or low levels of confidence to our assessments, as follows:

• High confidence generally indicates that our judgments are based on high-quality information, and/or that the nature of the issue makes it possible to render a solid judgment. A “high confidence” judgment is not a fact or a certainty, however, and such judgments still carry a risk of being wrong.

• Moderate confidence generally means that the information is credibly sourced and plausible but not of sufficient quality or corroborated sufficiently to warrant a higher level of confidence.

• Low confidence generally means that the information’s credibility and/or plausibility is questionable, or that the information is too fragmented or poorly corroborated to make solid analytic inferences, or that we have significant concerns or problems with the sources."

A number of other agencies have adopted a similar approach, some of which are outlined here by Pherson and Pherson (pp.192-195). Meanwhile, the IPCC's guidance on expressing confidence suggests a scale based on a combination of the level of 'agreement' about the finding and the 'robustness' of the evidence (without specifying exactly what these mean).

Our survey of analysts also suggests that they take overall 'quality' into account when making confidence judgements. Some of the suggested interpretations of 'confidence' included:

"Reliability, trustworthiness, accuracy"

"Confidence means confidence in the methodology by which you've obtained [the judgement]"

"Confidence here means how well the probabilities are based on reliable statistics and good data samples."

In short, the idea that 'confidence' proxies for the quality of the evidential or methodological foundations for a judgement is a popular one.

Is it coherent?

That judgements formed using high-quality methods and evidence are likely to be superior in a number of respects to those formed using low-quality ones is true rather by definition. Indeed, how else are we to judge the quality of these factors?

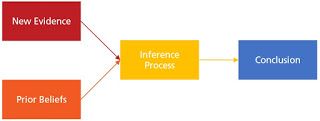

Quality-related theories of confidence encompass a range of factors that can be divided into three main categories: source- or data-related factors, method-related factors, and subject-matter expertise-related factors. These have effects we can understand in the context of the following idealised model of the components of judgement-formation.

Source- and data-related quality indicators pertain to the 'new evidence' box. They include a higher number of sources, higher reliability of those sources, a bigger sample size or duration, and (where possible) the use of more diagnostic data-generating processes such as randomised controlled trials. All of these factors have the same underlying effect: they make the data more discriminating and less noisy. All things being equal, information that is more discriminating will lead to a probability that is closer to 0 or 1, which is after all the aim of analysis.

Method-related quality indicators relate to the 'inference process' box. These include assurances that the method by which new evidence is used to update prior beliefs is a reasonable one that accords with the precepts of inference theory. In practice, this means having well-trained and bias-aware analysts, considering a wide range of hypotheses, and using of sound data-manipulation and hypothesis-testing methods.

Finally, expertise-related quality indicators relate primarily to the 'prior beliefs' box. Expertise can be thought of as a palimpsest of past data, reflected in a set of prior probabilities that are more discriminating. This gets the analytical party off to a better start by more-or-less eliminating possibilities that would otherwise have to be considered.

In short, the 'quality' theory of confidence can easily be given an interpretation that makes it entirely coherent with the principles of inference.

Is it decision-relevant?

Finally, is the quality of a judgement's provenance an important factor to decision-makers to take into account?

In short, no - at least, not by itself. The reason is that all of the factors comprised by the notion of 'quality' mediate themselves through the probability of the hypotheses under examination. In other words, better evidence, sounder methods and more expertise will be reflected in more discriminating probabilities. Since they are already incorporated in the probabilities attached to a judgement, communicating quality will not add anything to the motivation to act: a low-quality 70% is as good a reason for action as a high-quality one.

However, there may be an argument that 'quality' captures the extent to which analysis can be improved, by bundling together a host of factors that jointly give a sense of what, if anything, needs to be improved. For example, if we had sound methods and good data, but poor expertise, this may imply that all we need are a few experts to improve our analysis.

'Quality', then, may help suggest whether we should act now, or wait and do more analysis first, even if it doesn't affect our choice of actions when we do act. But it does this quite indirectly - knowing the quality of an analytical process doesn't actually tell you how costly it would be to improve, or whether it would be worth the effort.

Summary

The 'quality' theory of analytical confidence is a popular one, and can easily be made coherent with the theory of inference. By itself, it is not decision-relevant, but it may point towards the ease with which the picture can be improved before taking action. (We'll be looking at the 'Expected Cost' theory soon, which gives this idea a solo turn.)

In the next post, we'll look at the idea that 'confidence' measures the extent to which one's judgements are based on general background information compared to subject-specific data.